Bringing the United Nations Climate Change Negotiations Home to Maine

By

Ellie Johnston

June 13, 2018

This guest post was written by: Anna McGinn, Dr. Molly Schauffler, and Will Kochtitzky

The annual United Nations meeting to negotiate on climate change (called the Conference of the Parties—COP) is a whirlwind experience which fills one to the brim with climate change information. It almost feels like you have been transported to an alternate earth for two weeks where every country and everything we know about climate change exists within the bounds of a temporary conference center. To adequately and effectively communicate this experience to colleagues, community members, and friends is a challenge. It often feels like people have to experience the COP to digest how delegates from around the world come together to formulate something like the Paris Agreement. This is where the World Climate Simulation (WCS) comes in.

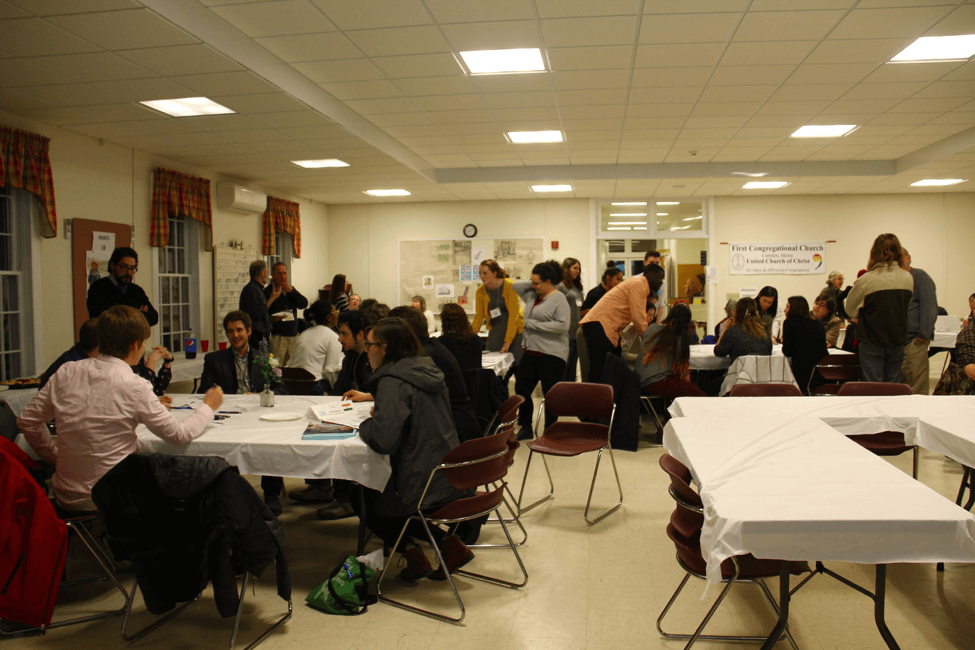

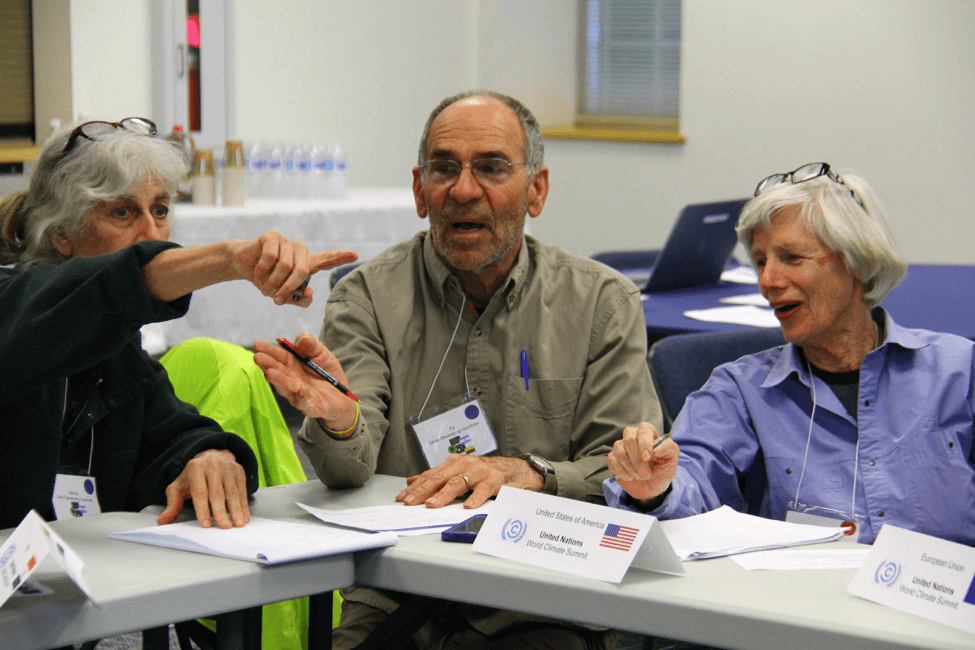

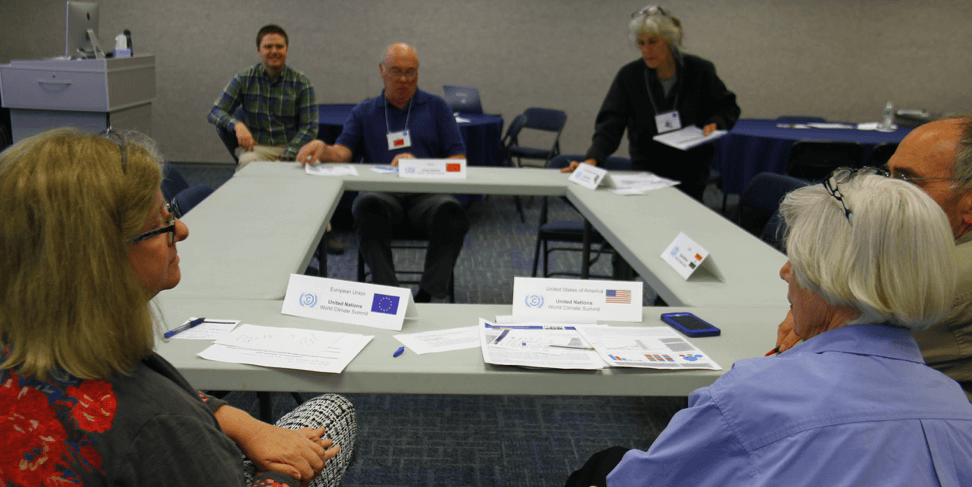

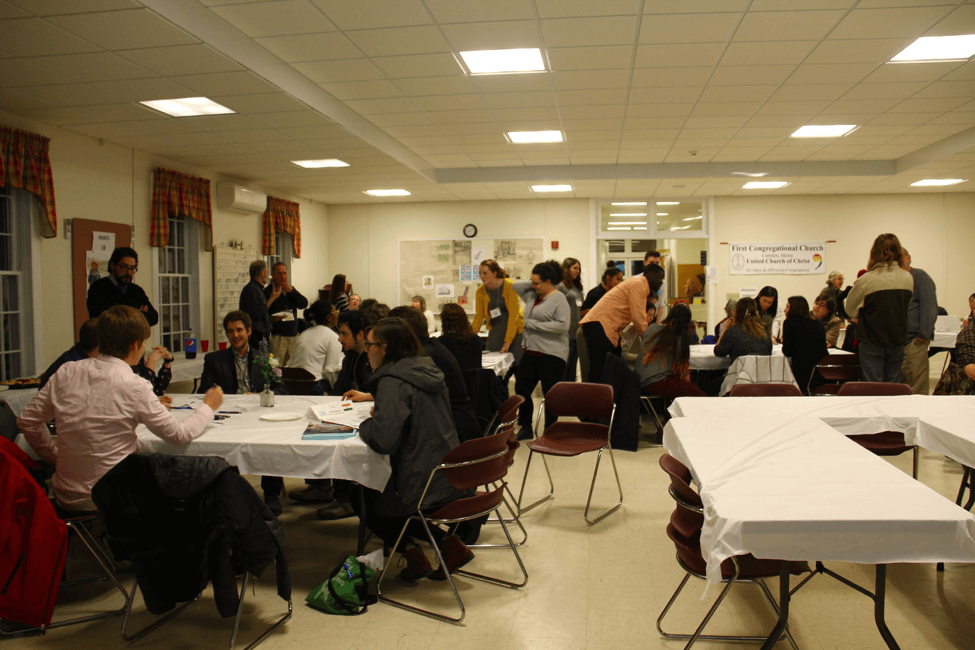

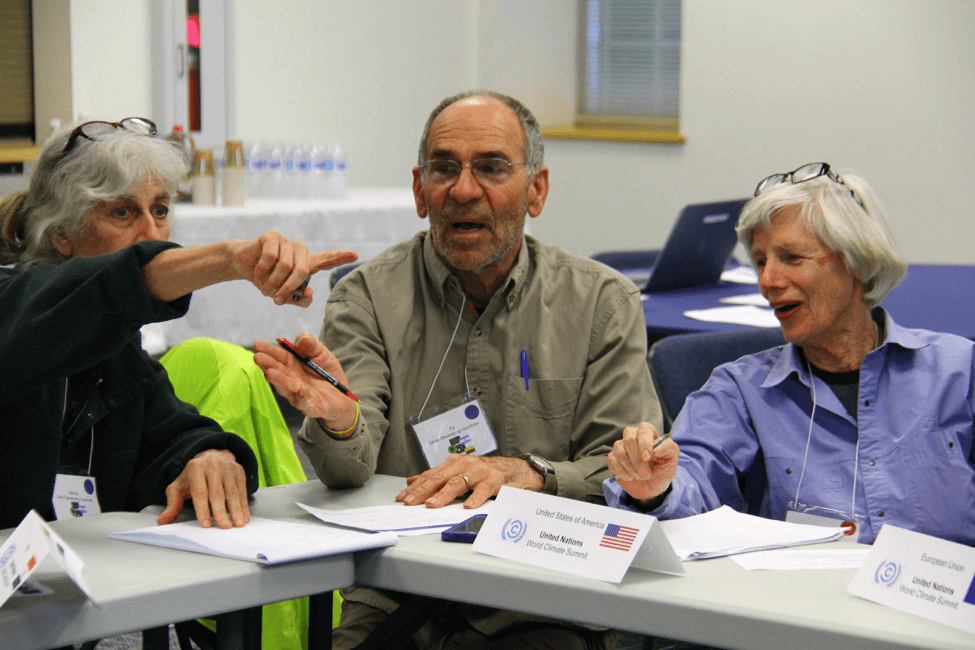

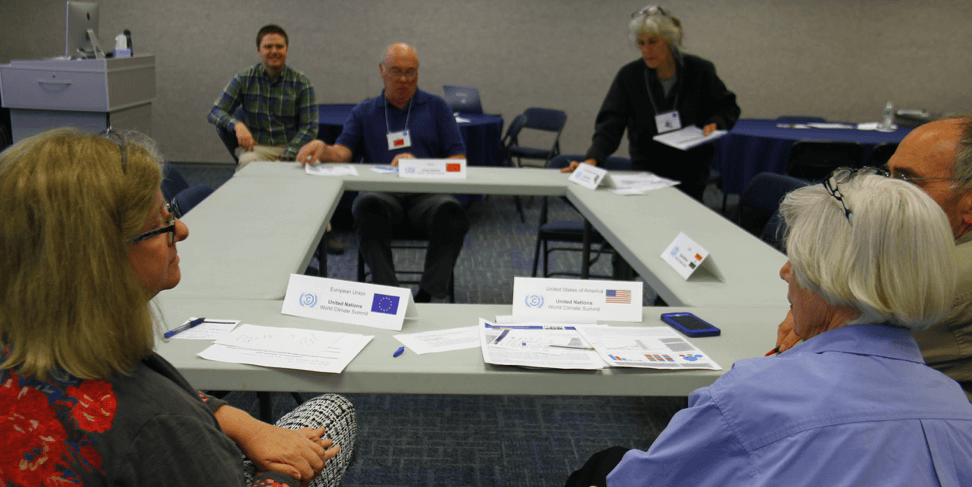

In November 2017, the University of Maine sent its first delegation to a UN climate change negotiating session—COP23 in Bonn, Germany. Upon returning to Maine, we planned UMaine’s first iteration of the WCS for the Climate Change Institute’s annual retreat. There we challenged 20 scientists to test out their international negotiating skills. What emerged was a collective realization that despite a deep knowledge of climate change—from physical, chemical, and biological perspectives—the group still could not reach an ambitious enough agreement to keep global average temperature rise “well below 2˚C.” Weighing scientific understanding with the complex economic, political, and social realities that factor into negotiations posed a big challenge for the group. Conversations about the simulation lingered for the remainder of the retreat, and highlighted the untapped potential for this type of climate change education in Maine.

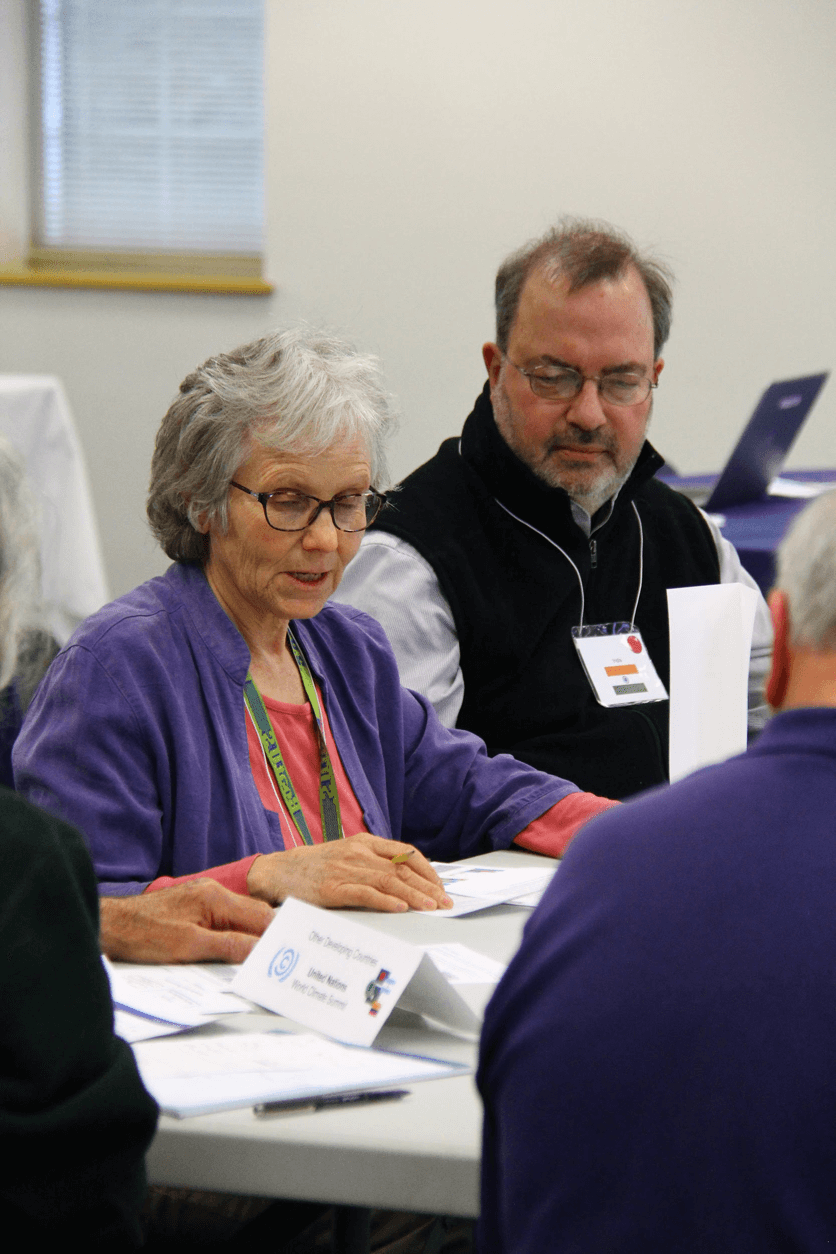

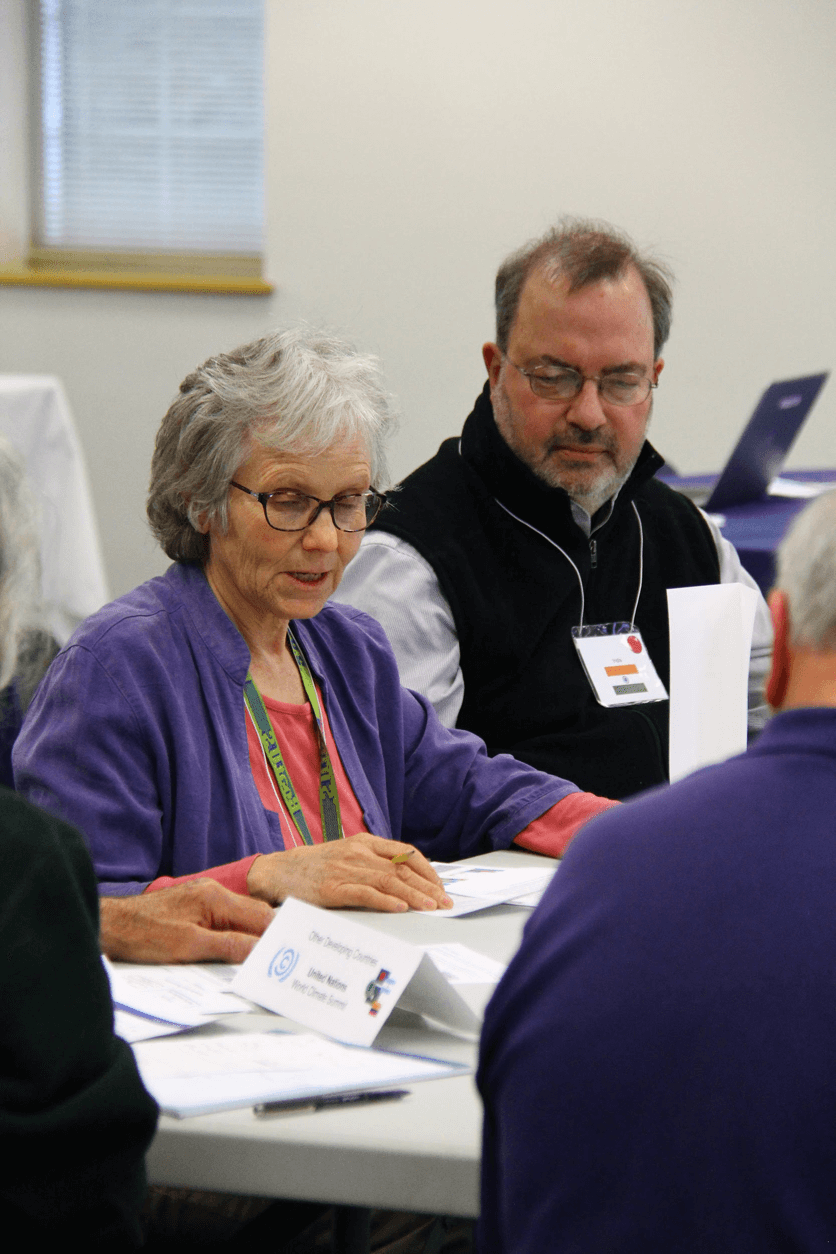

During the WCS participants continually asked a number of questions including: How do I know the amount of forest cover in my country? What is my country’s GDP? And how does my country rank in measures of inequality? Through these questions, we realized that people wanted to be accurate and detailed in their understanding of this process, which meant they needed data. This also seemed to be an opportunity—a way to leverage this exciting and interactive program to foster data literacy.

We developed a database using Tuva to pair with the WCS, and we set up “data centers” during our WCSs to give people access to this capacity building resource. At our following simulations at the 2018 Camden Conference, the Maine Science Teacher Association Annual Conference, and at the Hutchinson Center, access to additional country data created a new layer of debate and nuance. Our delegates were examining their historic deforestation rates and investigating their country’s dependence on different energy sources to bolster their negotiating platforms. We again saw the extent and the limits to which data driven arguments inform decision-making. As important as data are, reality often suggests that data do not always change people’s behavior—but stories do.

Since we starting utilizing the WCS, it has become clear that the simulation is an ideal way to communicate the complexity of the COPs to our communities back home in Maine. The program at the Hutchinson Center struck a chord with our participants who are now working to host a follow-on WCS in order to include town officials and groups from across the region. The exercise also acted as a launching pad for conversations about topics ranging from climate modeling to the possibilities of both local and global climate actions.

Building off this enthusiasm, we plan to continue to share the WCS with communities and schools in Maine to catalyze conversation on climate change. While attending COP24 this coming December in Katowice, Poland, our UMaine group also plans to communicate back with the groups that participated in the WCS to share our experiences with them in real time.

About the Authors:

Anna McGinn is a master’s student at the University of Maine in the School of Policy and International Affairs and the Climate Change Institute. She studies climate change adaptation under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and has attended COP17 in Durban, South Africa, COP21 in Paris, France, COP22 in Marrakech, Morocco, and COP23 in Bonn, Germany.

Dr. Molly Schauffler is a professor at the University of Maine School of Earth and Climate Sciences, Center for Research in STEM Education, Hutchinson Center and the Climate Change Institute. She works with pre-service and in-service science teachers in Maine to study and support data literacy, and is a science education consultant for Tuva.

Will Kochtitzky is a master’s student at the University of Maine in the School of Earth and Climate Sciences and the Climate Change Institute. He is a glaciologist studying glacial instabilities, and has attended COP20 in Lima, Peru and COP23 in Bonn, Germany.